Alex Capri Interview: Full Transcript

The following interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Alex Capri is a former Senior Fellow and current Senior Lecturer in the Business School and Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy at the National University of Singapore (NUS). He has been based in Asia for 20 years, previously the Partner and Regional Leader of KPMG’s International Trade & Customs Practice in Asia-Pacific and previously a Director in PwC’s World Trade Management practice. He is also a research fellow at the Hinrich Foundation in Singapore, where he has authored essays on international trade, technology, and geopolitics.

His recent book, Techno-Nationalism: How It's Reshaping Trade, Geopolitics and Society, explores why nations are restricting the flow of strategic technologies and how the international system is bifurcating and reorganizing itself around American and Chinese spheres of influence. You can purchase the book here.

Ted Osius

What is the premise of techno-nationalism, and how might it affect trade between ASEAN and the United States?

Alex Capri

Techno-nationalism is the linkage of a country's technology prowess through its major institutions and that of its national security, its economic strength, and its social stability.

Ted Osius

Is techno-nationalism equally relevant across countries, or are some regions more resistant to the paradigm?

Alex Capri

Every country, everywhere, is susceptible to the dynamics of techno-nationalism. Superpowers and the G7—plus countries that have been pulled directly into the U.S.-China geopolitical rivalry—will be affected in terms of the innovation race, the amount of money that gets focused on developing key strategic technologies. They will be involved in what I call the “technology feedback loop,” meaning that universities, defense establishments, private companies, and of course, key governments, will be directly interacting with each other.

The next grouping of countries are the middle-tier countries. These are countries that are very connected in global supply chains, but they're not major powers. I'm talking about countries in Southeast Asia, key economies like Malaysia, Singapore, Thailand, and Vietnam.

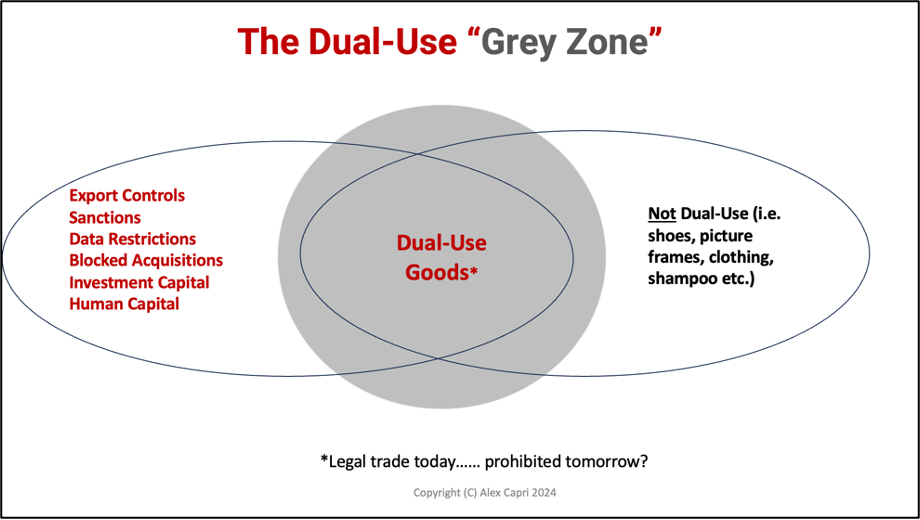

These countries are affected by techno-nationalism because they are now subject to export controls, technology control, and restrictions. They are now subject to the movement of people when it comes to foreign nationals—that is, which foreign nationals can work and have access to specific kinds of technologies. Increasingly, they've become subject to restrictions on data flows and data sovereignty issues. All that feeds back to the premise of techno-nationalism.

Ted Osius

From our perspective, since we focus on ASEAN, these nations are frontline.

Alex Capri

They are frontline. To take an example, Malaysia has been a focus for data center building, and it's also a key location in Southeast Asia for a portion of the semiconductor value chain around packaging and testing.

Up until this point, it's been a transit point, and it's also been a location that has attracted a lot of Chinese investment. Because of the decoupling phenomenon that's happening with China, you have multinational companies restructuring their supply chains out of China into neighboring countries in Southeast Asia. And, possibly even more importantly, we have Chinese companies relocating their operations.

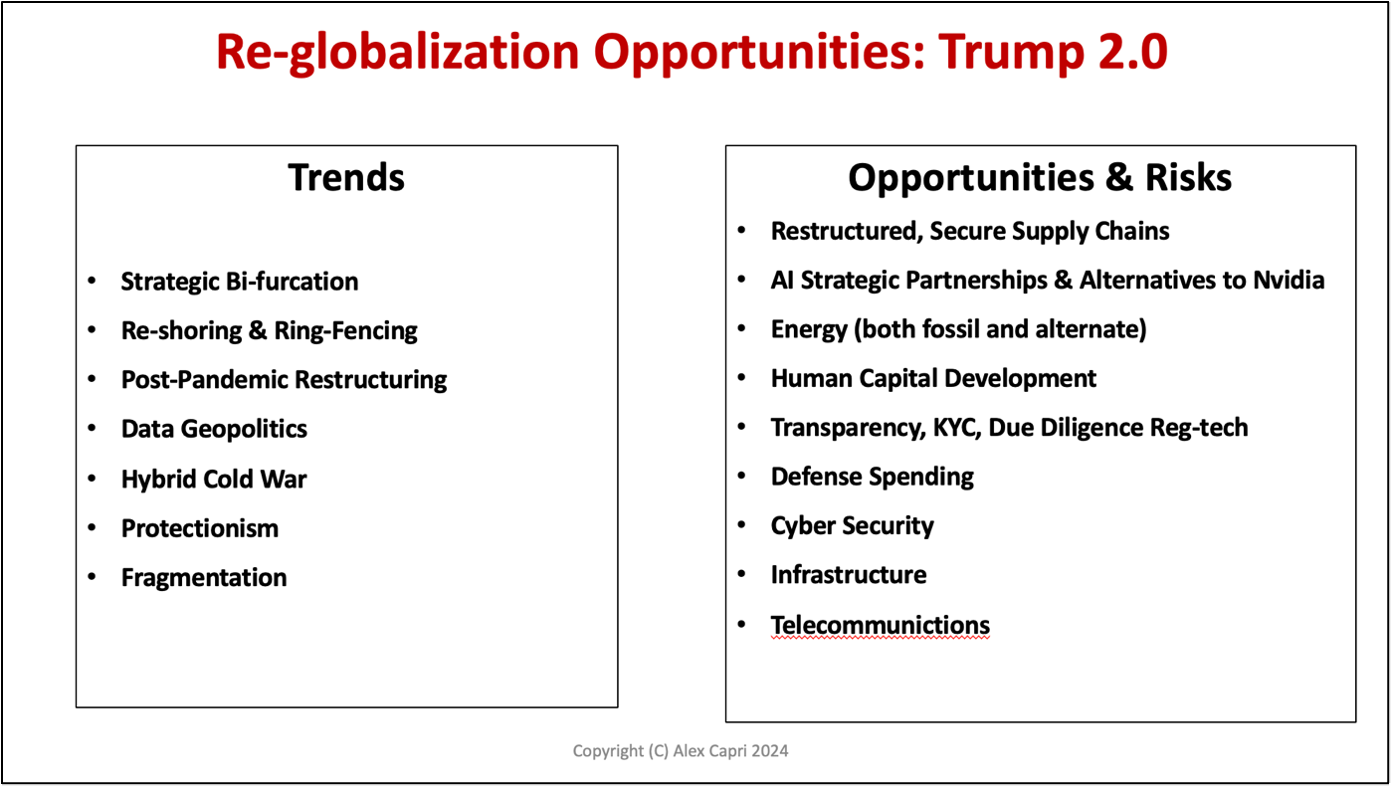

So now, as the techno-nationalist focus gets turned up a notch under Trump 2.0, countries like Malaysia, Vietnam, Singapore, and Mexico are going to be put under the spotlight. The Trump administration is going to be looking at whether technology gets blocked and whether this technology continues to get access to these middle-tier country markets. I think Southeast Asia is going to go through a period of uncertainty—we don't know exactly how this is going to play out.

Ted Osius

One of the things that’s so great about the book is that it describes not only how this came about, but also the historic context in which it came about. I urge those who are reading this interview to dig into some of the examples that Alex has provided that show why this is so acute.

But let me go on to the next question. Because you talk a lot about the opportunities of public-private partnerships, what role would those PPPs and corporate diplomacy play in the shifting global economic order?

Alex Capri

From an innovation perspective and from a competitiveness perspective, governments are looking to get ahead to win the innovation race, and the only way to do that now is to have the right combination of partners. So, you need governments to provide that seed money where the risks are too high for private commercial interest to take—the timeline might be too long before there's a return, if there even is a return.

Take, for example, the push to re-shore critical mineral processing back to North America to build up capabilities. From a techno-nationalist perspective, that's a decades-long process for most rare earth mining and processing. If it were not for government money, it just wouldn't be profitable. It's a very complex, very expensive process. It's essentially a type of public good that needs to be provided by governments. The Australian company Lynas is one of the only companies that is now able to extract rare and some critical minerals, but it's still dependent on China to a large degree for processing.

To get that process totally re-shored is going to be very expensive, so the public-private partnership element is critical. And then, of course, the firms that are involved are going to have specific expertise.

Ted Osius

I have to ask about DeepSeek. I think some governments think, “Instead of developing these very difficult-to-develop chips that are required for advanced artificial intelligence, we can just use something much simpler, because DeepSeek has shown the way.” What do you say to the folks who say that?

Alex Capri

I think there are some caveats there. DeepSeek is a large language model; it's a generative AI model that deals with text and can create software. From a technological standpoint, they used a technique called distilling. They took ChatGPT data that was open source, and they distilled it down using generative AI. They didn't imitate outright, but they iterated. And they stockpiled 10,000 Nvidia chips to do their initial setup, with many insisting that DeepSeek remains more dependent on Nvidia then advertised.

The question then becomes, can other middle countries infer that the DeepSeek “breakthrough” will allow them to sidestep the need for advanced chips and not have to worry about U.S. export controls and chokepoints in their own technology value chains? And if that's the case, then that's a game changer, right? That clearly diminishes the leverage that the U.S. has on controlling these chokepoints on vital chip-making technology for advanced chips.

Absent a genuine DeepSeek AI breakthrough, when it comes to advanced semiconductors, I would say that overall, the United States—and a handful of other U.S.-friendly nations such as the Netherlands and Japan—probably have a 10-to-15-year lead when it comes to value chains that account for the world’s most advanced chips. This will hold until somebody else figures out how to build the insanely complex “chokepoint” critical machinery, tooling, and chemicals or comes up with some alternative method for large-scale production of advanced chips.

Ted Osius

Maybe this is one of the many 21st century examples of what used to happen back in the early days of this republic, where we would steal the intellectual property of Great Britain to advance our industry. Germany is another example. But in the 21st century, it's become an incredibly lucrative game to skip the R&D stage by stealing somebody else's technology.

Alex Capri

It's massive. In the book, I use the example of how China’s tech-enabled tradecraft was used to steal vast amounts of America’s leading military technology. One story I use to put this in perspective is the example of stealth technology. Starting with America’s so-called Skunk Works program—which goes all the way back to the Second World War—it took decades of trial and error and billions of dollars to deliver the technology that eventually allowed U.S. forces to carry out a raid on Osama bin Laden’s secret complex in Pakistan, which killed him and netted massive amounts of intel.

Through their contacts with Pakistani officials, the Chinese were able to get their hands on the tail section of one of the helicopters used in the raid, which yielded a treasure trove of materials and secrets. They paired that with a very successful and deep cyber-intrusion operation. Using technology, they essentially penetrated every element of the U.S. defense establishment, from government to corporate. When you have access to that kind of information—in addition to supercomputing and the generative AI that enabled DeepSeek—you can take a lot of that information and innovate off it. You can create a great deal of very powerful technologies using that. Tradecraft and techno-nationalism go hand in hand.

Ted Osius

I strongly urge people to read the chapter on the bin Laden raid to understand the nature of the steal that's going on. You must have had incredible sources to be able to put together that part of the book.

Alex Capri

The best source was WikiLeaks—that was an absolute goldmine. It involved hundreds of thousands of government memos and communiques. What the leaked information revealed was that it was long known within the U.S. government, across many different agencies, just how pervasive China’s cyber-intrusions had been. But there was also this sense of helplessness because there was just no way to stop it.

There are so many weapon systems that were literally cloned. The entire F-35 program has now been transmitted over to the Chinese, as well as the Patriot missile defense system, and on and on. Yet the technology that was used to gain access to these systems with proprietary and sensitive information was not that sophisticated.

Ted Osius

Let's go back to Southeast Asia as a growing hub for data centers and semiconductor manufacturing. How can Southeast Asia most effectively navigate heightened global trade tensions in the field of critical technologies and artificial intelligence?

Alex Capri

That’s the million-dollar question. The endgame is to try to avoid a binary choice. If you're Singapore, Malaysia, or any country, the question is, “Can we retain agency? And can we trade with as many people as possible and not have to worry about being coerced into behaving one way or the other?”

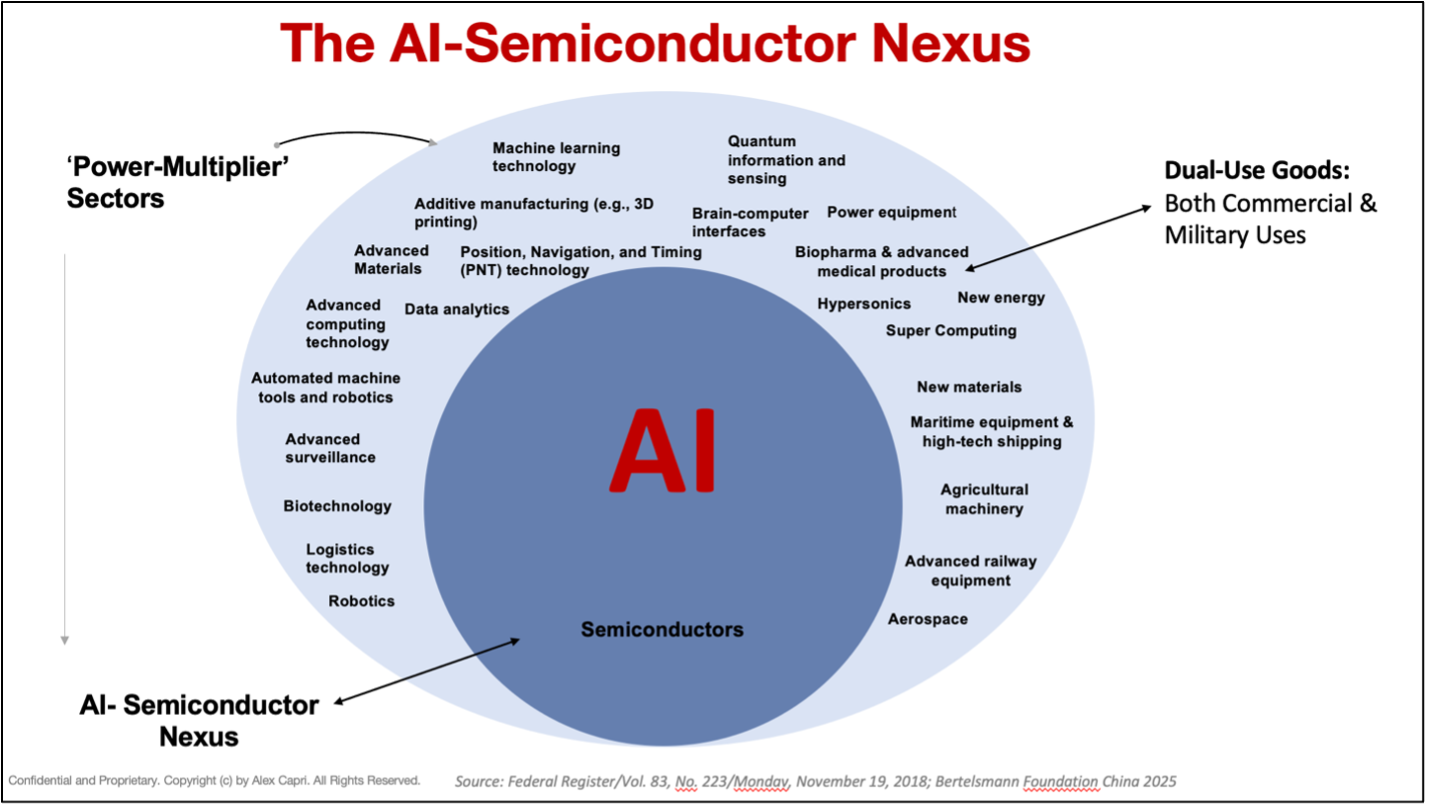

This is most acute in the technology stacks around the “semiconductor-AI nexus” and how this relates to data centers and the cloud. The link is between AI—which, again, is dependent on semiconductors—and this burgeoning area of data centers. When we think of the cloud, we tend to think of something up in the ether, right? But 99% of the data in the cloud passes through physical fiber-optic undersea cables.

Ted Osius

That's the critical infrastructure.

Alex Capri

All of that is now an existential issue for middle countries—countries in Southeast Asia in particular—who are faced with a binary choice. They must choose who's building their critical technology stacks and their critical infrastructure.

So why is this DeepSeek issue so important? Because the question is: how much can a middle country like Malaysia, for example, continue to build data centers without having to rely on leading-edge Nvidia chips or other world-leading U.S. tech companies, which are subject to Washington’s supply chain weaponization designs? How much can a small country innovate on its own? How complex of a system of infrastructure can you run using the technology that DeepSeek rolled out? That’s an outcome that could have a big effect, potentially on Southeast Asia.

Ted Osius

Given the growing number of countries banning the use of certain mobile applications—TikTok and potentially DeepSeek—and introducing age restrictions for social media—Australia and Indonesia come to mind—how do you foresee the development of the relationship between large tech companies and the governments of their host countries?

Alex Capri

Good question. I do think that we're going to see more attempts to regulate big tech. And here is where I think there's going to be an interesting paradox: there's a need to regulate big tech because of mental health concerns. There are, from a techno-nationalist standpoint, concerns around censorship and narrative, including influence campaigns and disinformation campaigns. There's that hybrid warfare element—these big technology companies are strategic assets from a techno-nationalist standpoint.

Big tech is very important to governments as they build hard infrastructure around AI, so there are symbiotic relationships that are directly linked to techno-nationalism. But then there are the tensions and frictions that will come, so there's no zero-sum game anywhere in all of this. It's just all over the place, and that's just the world that we must get used to. It's a much more complex world.

Ted Osius

Well, they're certainly seen as strategic assets in the United States. Witness who attended President Trump's inauguration.

But in Southeast Asia, there are also the companies that each of those nations wants to attract the most. There's this understanding that if you're going to move up from low value-added manufacturing to an innovation economy, you need those assets. You need the data centers and the ecosystems that are created around these big tech companies. Some countries have a head start—I think of Malaysia having attracted investment since the 1970s, which makes it hard for the newbies to catch up.

Alex Capri

Digital trade is also driving economic growth in the informal economy—what we would call de minimis transactions from a taxation standpoint. Lots of small transactions are empowered by social commerce. All these platforms are driving economic growth domestically and locally within small niches. These platforms, like TikTok, are integral to commerce in many ways. You can't ignore that.

I'll let you in on some of the stuff that I'm looking at now, and that is this idea of anonymity on the web and the shortfalls of anonymity—everything from fake news to fraud. I think we're going to start seeing a stratification of the digital commerce landscape in some of the more forward-thinking countries.

It's almost like the “sesame credit” system in China—the way that, based on your complete digital footprint and the visible actions that you take, you get rated. A government can use all your personal data to reward you or punish you for either behaving or not behaving according to their desires. Because of your point score, you might get a better rate at the bank or get a discount on your airline tickets, or you might be denied a bank loan and banned from buying an airline ticket. Although China uses this system in a techno-authoritarian way—and I don't approve of the way it's being exercised—I do think that, to deal with a lot of the problems with social media, there's going to be a stratification around privacy and anonymity when it comes to the activities that you engage in on the web. This debate will inform techno-nationalist behavior.

Ted Osius

It’s interesting how, during Covid, every business that wasn't online went online. In some ways, Covid was democratizing. I think you're onto something regarding this stratification. There's a race now, and we don't want to be the ones left behind as this stratification occurs.

Alex Capri

I’ve talked about the key elements of techno-nationalism: weaponization of supply chains; de-risking and decoupling; reshoring, near-shoring and ringfencing; innovation; mercantilism, with governments competing against each other; and tech-diplomacy.

In this techno-nationalist environment, there are winners and losers. In the short term, the losers might be those that have high sunk costs and now must shift their supply chains for geopolitical reasons. Many companies are trying to avoid that. But I think it was Colin Powell who said, “bad news is bad news no matter when you hear it,” right?

The bad news is that some companies are simply going to have to decouple from China. Others will de-risk, but on the flip side of that, when you think about all this restructuring and reshoring, there’s a lot of money to be made. There are a lot of companies that are going to build these new supply chains. They're going to provide services, build infrastructure, underwrite it, and loan money.

Any kind of transition means that some people are going to capitalize on cybersecurity. Companies are going to have to start looking at cybersecurity in ways that they never imagined. Because nothing is secure, right? If you think WhatsApp is secure, think again. That's a growth industry.

If I had to sum up where I think this techno-nationalist dynamic is pushing industry, it’s going to involve what I call the “five Ts.” You need trust and truth for any successful business endeavor or any relationship. And to do that, you need technology. You need talent. And, of course, you need transparency. And then, actually, you can achieve the sixth “T,” which would be traceability.

Ted Osius

Opportunities arise from the risks and challenges of techno-nationalism. This is fascinating. Your book is superb. I think you're a terrific teacher, and you make complicated subjects understandable. I urge those who read this interview to get this book and study it. It's going to help you discover what both the challenges and the opportunities are of this global phenomenon that's affecting pretty much every business on the planet. Thank you.

Alex Capri

Thank you very much, Ambassador Osius. It’s been a pleasure.